Gulliver’s Travels (1939)

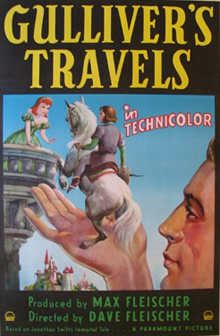

After Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” became the top grossing picture of 1938, Paramount Pictures turned to Disney’s best known competitor, Max Fleischer (animator of the hugely popular Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons) for an animated feature of its own. That was the good news for Fleischer. The bad news was the studio wanted it in less than a year, and “Snow White” had taken three years to complete. Turning to Irish satirist Jonathan Swift’s fantasy classic -- which, strangely enough, had already been transformed into a pro-Communist parable by stop-motion animators in the Soviet Union -- Max and brother Dave Fleischer discarded their original concept of using Popeye as their Gulliver. Instead, they went with a conventionally heroic characterization, relying on timesaving rotoscopes of actor Sam Parker. (If you’re unfamiliar with the concept, rotoscoping was an animation process invented by Max Fleischer that involved tracing over filmed images.) The rushed production was marked by innumerable problems, including a bitter feud between west coast and east coast animators. While no gunplay resulted from the cartoony clash, it didn’t help the final result. When the film was released at Christmas, critics were unimpressed, but the Fleischer shop’s visual invention and broad comedy was enough to make the film a hit; animated features were still very much a novelty and Paramount’s gamble actually paid off. A follow-up film, the fanciful musical bug fable, “Hoppity Goes to Town” might have done as well. But it was released on Dec. 9, 1941 -- two days after Pearl Harbor was attacked. These days, “Gulliver’s Travels” gets mixed reviews from animation fans, but at least it’s not hard to see. It has fallen into the public domain and is available on several different DVD editions and even for free, legal

downloads. Have at it. –

Bob Westal Animal Farm (1954)

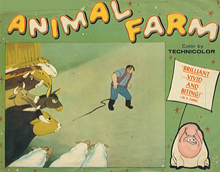

Wanna make your toddler grow up real quick? Set the little dickens down in front of the television and put “Animal Farm” in the DVD player. Anyone who read the original source material – George Orwell’s 1945 book of the same name – will already know what horrors they’re embarking upon. But the uninitiated might be shocked at the way Orwell’s political allegory has been transformed by British animators into a blend of Disney-esque animation and moments of legitimate horror, the latter aided immeasurably by Matyas Seiber’s score. The nutshell summary involves a barnyard’s worth of animals that get fed up with the drunken farmer who ostensibly cares for their well-being, and decide to run him out and take control of the farm. Things start out reasonably enough, with the declaration from the elder pig Old Major (inspired by some combination of Marx and Lenin) that “all animals are equal,” but upon his death, another pig named Napoleon (a thinly veiled version of Joseph Stalin) takes the reigns of command and soon adjusts the declaration to include a caveat: “But some animals are more equal than others.” This is definitely not a film for the kiddies. Not only is there acknowledgment of the death of some of the animals during the course of the coup, but when one of the ruling pigs tells the chickens that their eggs will be taken as trade goods, the chickens’ subsequent rebellion results in another motto adjustment: “No animal shall kill another animal…without cause.” In the blood of the chickens! (Let’s not even discuss how Boxer the horse gets a one-way ticket to the glue factory.) The ending of the film is different from the book, offering a successful counter-revolution against Napoleon’s rule. Hmmm, you don’t think that’s because the CIA helped fund the film, do you?

Wanna make your toddler grow up real quick? Set the little dickens down in front of the television and put “Animal Farm” in the DVD player. Anyone who read the original source material – George Orwell’s 1945 book of the same name – will already know what horrors they’re embarking upon. But the uninitiated might be shocked at the way Orwell’s political allegory has been transformed by British animators into a blend of Disney-esque animation and moments of legitimate horror, the latter aided immeasurably by Matyas Seiber’s score. The nutshell summary involves a barnyard’s worth of animals that get fed up with the drunken farmer who ostensibly cares for their well-being, and decide to run him out and take control of the farm. Things start out reasonably enough, with the declaration from the elder pig Old Major (inspired by some combination of Marx and Lenin) that “all animals are equal,” but upon his death, another pig named Napoleon (a thinly veiled version of Joseph Stalin) takes the reigns of command and soon adjusts the declaration to include a caveat: “But some animals are more equal than others.” This is definitely not a film for the kiddies. Not only is there acknowledgment of the death of some of the animals during the course of the coup, but when one of the ruling pigs tells the chickens that their eggs will be taken as trade goods, the chickens’ subsequent rebellion results in another motto adjustment: “No animal shall kill another animal…without cause.” In the blood of the chickens! (Let’s not even discuss how Boxer the horse gets a one-way ticket to the glue factory.) The ending of the film is different from the book, offering a successful counter-revolution against Napoleon’s rule. Hmmm, you don’t think that’s because the CIA helped fund the film, do you?

– Will Harris

Gay Purr-ee (1962)

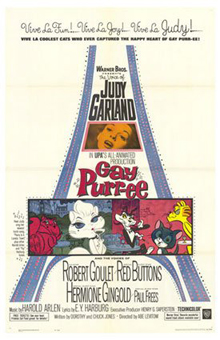

Say what you will about “Gay Purr-ee,” but one thing’s for certain: there isn’t another animated film that looks quite like it. Set in turn-of-the-century France, the story revolves around a cat named Mewsette (Judy Garland) who grows weary of her boy-toy, Jaune Tom (Robert Goulet), and heads from her farm in Provence to see the bright, exciting lights of Paris. Not one to be abandoned, Jaune Tom goes after her, with his little kitten buddy, Robespierre (Red Buttons), in tow. Before they catch up, Mewsette is discovered by Meowrice (voiced with all due sleaziness by the great Paul Frees), who has her groomed to perfection in order to make her the mail-order bride of a cat in -- gasp! -- Pittsburgh. Fans of Garland’s work in “The Wizard of Oz” will also be interested to learn that Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg wrote the songs in both that film and “Gay Pur-ee.” (Don’t get too excited: these songs definitely aren’t up to the standards set by “Oz.”) Though its characters may possess the inevitable visual hallmarks of a Chuck Jones production, the backgrounds are another story entirely. Taking advantage of the timeframe and locale of the film, Jones based the landscapes on Impressionist and Post-Impressionist styles of painting, borrowing liberally from Monet and Renoir. There are also tributes to Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Toulouse Lautrec, and Paul Gauguin, plus the awful but inevitable cat-related puns like the Felines Bergere or the Mew-lon Rouge. Today’s kids might be bored by the comparatively staid animation style, but if you’re an art lover, you’ll get a kick out of “Gay Purr-ee.” – Will Harris

Say what you will about “Gay Purr-ee,” but one thing’s for certain: there isn’t another animated film that looks quite like it. Set in turn-of-the-century France, the story revolves around a cat named Mewsette (Judy Garland) who grows weary of her boy-toy, Jaune Tom (Robert Goulet), and heads from her farm in Provence to see the bright, exciting lights of Paris. Not one to be abandoned, Jaune Tom goes after her, with his little kitten buddy, Robespierre (Red Buttons), in tow. Before they catch up, Mewsette is discovered by Meowrice (voiced with all due sleaziness by the great Paul Frees), who has her groomed to perfection in order to make her the mail-order bride of a cat in -- gasp! -- Pittsburgh. Fans of Garland’s work in “The Wizard of Oz” will also be interested to learn that Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg wrote the songs in both that film and “Gay Pur-ee.” (Don’t get too excited: these songs definitely aren’t up to the standards set by “Oz.”) Though its characters may possess the inevitable visual hallmarks of a Chuck Jones production, the backgrounds are another story entirely. Taking advantage of the timeframe and locale of the film, Jones based the landscapes on Impressionist and Post-Impressionist styles of painting, borrowing liberally from Monet and Renoir. There are also tributes to Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, Toulouse Lautrec, and Paul Gauguin, plus the awful but inevitable cat-related puns like the Felines Bergere or the Mew-lon Rouge. Today’s kids might be bored by the comparatively staid animation style, but if you’re an art lover, you’ll get a kick out of “Gay Purr-ee.” – Will Harris

The Incredible Mr. Limpet (1964)

The time-honored tradition of taking animated characters and placing them within an otherwise live-action movie was far from new in 1964, but rarely had they been utilized within such a completely bizarre premise. Don Knotts – who looks vaguely cartoonish, anyway – plays Henry Limpet, a henpecked office drone with a fish fetish. He loves them so much that not only does he carry around a book about reverse evolution (in the hopes that someday the human race might devolve back into fishes), but he even finds himself gazing into his aquarium and singing, “I wish, I wish, I wish I were a fish.” No surprise here: his wish is granted, which proves surprisingly upsetting for Bessie, Henry’s complete shrew of a wife. (She’s so awful to him that you’d think she would’ve said, “Good riddance!”) Knotts’ transformation doesn’t occur until 22 minutes into the film, but once it does, “The Incredible Mr. Limpet” begins a fun-filled voyage under the sea and finds Henry battling sharks, barracudas, and -- Nazis? Don’t worry, Mom and Dad: even Sgt. Schultz could outwit the German naval officers we find in the film. There’s no question that this is a family film, although one can imagine how many parents were scrambling for the theater exits when their kids asked, “What’s a spawning ground?” Paul Frees offers a great vocal performance as Crusty the hermit crab that isn’t so far removed from Yosemite Sam, while Elizabeth MacRae (best known for playing Gomer Pyle’s girlfriend, Lou-Ann) provides the voice of Henry’s fishy love interest, known simply as Ladyfish. For such a silly film, there’s an oddly poignant line at the end of the film when Bessie sees Henry as a fish for the first time and asks, “Am I the widow of a man or the wife of a fish?” Knotts offers up the bittersweet reply, “It’s not as though you can keep me in the bathtub, now, is it?” And with that, Mr. Limpet swims into the sunset, bringing an end to a slight but still enjoyable cult classic of the ‘60s. – Will Harris

The time-honored tradition of taking animated characters and placing them within an otherwise live-action movie was far from new in 1964, but rarely had they been utilized within such a completely bizarre premise. Don Knotts – who looks vaguely cartoonish, anyway – plays Henry Limpet, a henpecked office drone with a fish fetish. He loves them so much that not only does he carry around a book about reverse evolution (in the hopes that someday the human race might devolve back into fishes), but he even finds himself gazing into his aquarium and singing, “I wish, I wish, I wish I were a fish.” No surprise here: his wish is granted, which proves surprisingly upsetting for Bessie, Henry’s complete shrew of a wife. (She’s so awful to him that you’d think she would’ve said, “Good riddance!”) Knotts’ transformation doesn’t occur until 22 minutes into the film, but once it does, “The Incredible Mr. Limpet” begins a fun-filled voyage under the sea and finds Henry battling sharks, barracudas, and -- Nazis? Don’t worry, Mom and Dad: even Sgt. Schultz could outwit the German naval officers we find in the film. There’s no question that this is a family film, although one can imagine how many parents were scrambling for the theater exits when their kids asked, “What’s a spawning ground?” Paul Frees offers a great vocal performance as Crusty the hermit crab that isn’t so far removed from Yosemite Sam, while Elizabeth MacRae (best known for playing Gomer Pyle’s girlfriend, Lou-Ann) provides the voice of Henry’s fishy love interest, known simply as Ladyfish. For such a silly film, there’s an oddly poignant line at the end of the film when Bessie sees Henry as a fish for the first time and asks, “Am I the widow of a man or the wife of a fish?” Knotts offers up the bittersweet reply, “It’s not as though you can keep me in the bathtub, now, is it?” And with that, Mr. Limpet swims into the sunset, bringing an end to a slight but still enjoyable cult classic of the ‘60s. – Will Harris

Pinocchio in Outer Space (1965)

Some titles demand your attention. Such is the case with “Pinocchio in Outer Space.” Whether you actually care about the answer or not, you still immediately find yourself asking, “Hey, how the hell did Pinocchio get into outer space?” Well, let’s just say there’s a lot of suspension of disbelief involved (expect to ignore virtually everything you ever learned in science class), but this Belgian-American collaboration is certainly a trip worth taking -- just as long as you’re not looking for a spot-on sequel to the Disney film. Thank goodness the character of Pinocchio wasn’t owned by Walt and company, eh? “Pinocchio in Outer Space” picks up mere months after Carlo Collodi’s original story ended, but, man, has the kid done a serious backslide! Despite being granted boyhood by the Blue Fairy, Pinocchio went back to his old ways, and the result was getting dumped right back into puppet form. Once we get this information, we instantly suspect that the film will end like its predecessor, with Pinocchio becoming a real boy once more. But even so, who could’ve foreseen that the plot would also involve an alien turtle named Nurtle (voiced by Arnold “Top Cat” Stang) and a marauding intergalactic whale named Astro? Sorry, no Jiminy Cricket this time; he’s a Disney creation. The best part of Pinocchio’s space exploration involves his trip to Mars. The design is darkly gorgeous, the action is thrilling, and some of the sci-fi concepts that are posited are sufficient to blow most kids’ minds. Really, though, just knowing that it features both an atomic blast and a chirpy little ditty called “It’s A Goody Good Morning” should be sufficient to inspire a rental.

Some titles demand your attention. Such is the case with “Pinocchio in Outer Space.” Whether you actually care about the answer or not, you still immediately find yourself asking, “Hey, how the hell did Pinocchio get into outer space?” Well, let’s just say there’s a lot of suspension of disbelief involved (expect to ignore virtually everything you ever learned in science class), but this Belgian-American collaboration is certainly a trip worth taking -- just as long as you’re not looking for a spot-on sequel to the Disney film. Thank goodness the character of Pinocchio wasn’t owned by Walt and company, eh? “Pinocchio in Outer Space” picks up mere months after Carlo Collodi’s original story ended, but, man, has the kid done a serious backslide! Despite being granted boyhood by the Blue Fairy, Pinocchio went back to his old ways, and the result was getting dumped right back into puppet form. Once we get this information, we instantly suspect that the film will end like its predecessor, with Pinocchio becoming a real boy once more. But even so, who could’ve foreseen that the plot would also involve an alien turtle named Nurtle (voiced by Arnold “Top Cat” Stang) and a marauding intergalactic whale named Astro? Sorry, no Jiminy Cricket this time; he’s a Disney creation. The best part of Pinocchio’s space exploration involves his trip to Mars. The design is darkly gorgeous, the action is thrilling, and some of the sci-fi concepts that are posited are sufficient to blow most kids’ minds. Really, though, just knowing that it features both an atomic blast and a chirpy little ditty called “It’s A Goody Good Morning” should be sufficient to inspire a rental.

– Will Harris

The Daydreamer (1966)

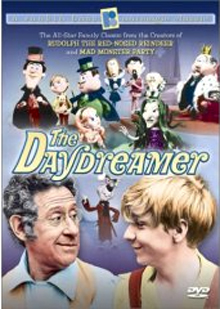

Good ol’ Rankin-Bass. Not long after the success of 1964’s Animagic (puppet animation) TV special, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” they made their first attempt at a full-length motion picture with the Animagic “Willie McBean & His Magic Machine,” which may be too obscure even for this article. Later, there was 1967’s cell-animated “The Wacky World of Mother Goose.” In between, however, there was 1966’s “The Daydreamer.” By far the most ambitious Rankin-Bass production, the film tells the story of “Chris” (Paul O’Keefe), presumably the young Hans Christian Anderson. When Chris drops off to sleep, he has a series of stop-motion encounters drawn from Anderson’s based known stories, including “Thumbelina,” “The Emperor’s New Clothes” and, 23 years before Disney would take a crack at it, “The Little Mermaid.” Executive produced by flamboyant independent film impresario Joseph E. Levine, the “all-star” live action cast included character actor Jack Gilford (famous throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s for a series of Cracker Jack commercials), as well as cameos by Ray Bolger and Margaret Hamilton -- a.k.a., the Scarecrow and the Wicked Witch of the West from “The Wizard of Oz.” The voice cast included ‘60s teen faves Hayley Mills and Patty Duke, singing heartthrob Robert Goulet, and such legendary hams as Tallulah Bankhead, Burl Ives and Boris Karloff. Despite all the semi-big-name talent, the film apparently failed to attract any attention at all and was mostly seen at kiddie matinees. Even today, its DVD release doesn’t seem to impress anyone very much, though there are always those great Rankin-Bass character designs to fall back on. Right? – Bob Westal

Good ol’ Rankin-Bass. Not long after the success of 1964’s Animagic (puppet animation) TV special, “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” they made their first attempt at a full-length motion picture with the Animagic “Willie McBean & His Magic Machine,” which may be too obscure even for this article. Later, there was 1967’s cell-animated “The Wacky World of Mother Goose.” In between, however, there was 1966’s “The Daydreamer.” By far the most ambitious Rankin-Bass production, the film tells the story of “Chris” (Paul O’Keefe), presumably the young Hans Christian Anderson. When Chris drops off to sleep, he has a series of stop-motion encounters drawn from Anderson’s based known stories, including “Thumbelina,” “The Emperor’s New Clothes” and, 23 years before Disney would take a crack at it, “The Little Mermaid.” Executive produced by flamboyant independent film impresario Joseph E. Levine, the “all-star” live action cast included character actor Jack Gilford (famous throughout the ‘60s and ‘70s for a series of Cracker Jack commercials), as well as cameos by Ray Bolger and Margaret Hamilton -- a.k.a., the Scarecrow and the Wicked Witch of the West from “The Wizard of Oz.” The voice cast included ‘60s teen faves Hayley Mills and Patty Duke, singing heartthrob Robert Goulet, and such legendary hams as Tallulah Bankhead, Burl Ives and Boris Karloff. Despite all the semi-big-name talent, the film apparently failed to attract any attention at all and was mostly seen at kiddie matinees. Even today, its DVD release doesn’t seem to impress anyone very much, though there are always those great Rankin-Bass character designs to fall back on. Right? – Bob Westal

The Man Called Flintstone (1966)

Remember the days when successful TV cartoons could spawn theatrical films and not just straight-to-video clunkers? Probably not. But in the 1960s, Hanna Barbera took advantage of the opportunity to pick up the kiddie-matinee crowds by releasing full-length features starring both Yogi Bear and the Flintstones gang. There’s something impressive about the effort that went into “The Man Called Flintstone,” which arrived in theaters on the heels of the original “Flintstones” ending its network run. Granted, there isn’t a huge amount of new ground broken by the film’s plot, which blends “The Prince and the Pauper” with the spy genre by having Fred cross paths with a secret agent who just so happens to look exactly like him. Naturally, a situation arises where Fred is asked to take the agent’s place, resulting in Fred, Wilma, Barney, Betty, Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm traipsing around the world, with Fred trying to keep undercover by keeping everyone else in the dark. It’s evident from the backgrounds that William Hanna and Joe Barbera, who produced and directed the film, went out of their way to take advantage of the cinematic scope in the chase scenes. What doesn’t work as well are the attempts to shoehorn musical numbers into the flick, but the Bond-inspired theme song is genius, and there’s enough traditional “Flintstones” fun to make the film a highly enjoyable viewing experience for the show’s fans. – Will Harris

Remember the days when successful TV cartoons could spawn theatrical films and not just straight-to-video clunkers? Probably not. But in the 1960s, Hanna Barbera took advantage of the opportunity to pick up the kiddie-matinee crowds by releasing full-length features starring both Yogi Bear and the Flintstones gang. There’s something impressive about the effort that went into “The Man Called Flintstone,” which arrived in theaters on the heels of the original “Flintstones” ending its network run. Granted, there isn’t a huge amount of new ground broken by the film’s plot, which blends “The Prince and the Pauper” with the spy genre by having Fred cross paths with a secret agent who just so happens to look exactly like him. Naturally, a situation arises where Fred is asked to take the agent’s place, resulting in Fred, Wilma, Barney, Betty, Pebbles and Bamm-Bamm traipsing around the world, with Fred trying to keep undercover by keeping everyone else in the dark. It’s evident from the backgrounds that William Hanna and Joe Barbera, who produced and directed the film, went out of their way to take advantage of the cinematic scope in the chase scenes. What doesn’t work as well are the attempts to shoehorn musical numbers into the flick, but the Bond-inspired theme song is genius, and there’s enough traditional “Flintstones” fun to make the film a highly enjoyable viewing experience for the show’s fans. – Will Harris

Mad Monster Party (1969)

For years, this stop-motion horror spoof/musical comedy was remembered only by geeks of a certain stripe who had grown up in the Los Angeles area in the 1970s, which explains why we’re pretty sure a young Tim Burton must have seen it over and over again. Another stop-motion extravaganza in Animagic from the creative team of Rankin-Bass, “Mad Monster Party” is an obvious influence on “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” but it’s a fascinating slice of late ‘60s pop culture in its own right. Featuring the final screen “appearance” of horror icon Boris Karloff, “Mad Monster Party” was co-written by comics legend Harvey Kurtzman, creator of the original “Mad” comic books, and featured character designs by cartoonist Jack Davis of “Mad Magazine” and EC comics — a genius at combining humor and grotesquerie. The cast also features hair-challenged stand-up comic Phyllis Diller as “the monster’s mate,” pop singer/actress Gayle Garnett as Dr. Frankenstein’s sexy assistant, and voice actor Allen Swift, who performs dopey but amusing impressions of deceased horror stalwarts Peter Lorre and Bela Lugosi, as well as the silliest Jimmy Stewart this side of Dana Carvey (the voice of ultra-dweeb hero, Felix Flanken). Featuring shticky gags, a rock ‘n’ roll band of mop-topped skeletons, and surprisingly catchy ‘60s-style mainstream pop tunes by Maury Laws and director Jules Bass, “Mad Monster Party” is not quite a classic, but definitely required viewing for fans of great stop motion-animation and late-‘60s lunacy. It also has one of the stranger animation credits we’ve ever seen: “choreography by ‘Killer Joe’ Piro.” (Piro was a temporarily famous New York City dance teacher and disco habitué. Rankin-Bass was way too hip to use anything but the latest steps for its monsters.) – Bob Westal

For years, this stop-motion horror spoof/musical comedy was remembered only by geeks of a certain stripe who had grown up in the Los Angeles area in the 1970s, which explains why we’re pretty sure a young Tim Burton must have seen it over and over again. Another stop-motion extravaganza in Animagic from the creative team of Rankin-Bass, “Mad Monster Party” is an obvious influence on “The Nightmare Before Christmas,” but it’s a fascinating slice of late ‘60s pop culture in its own right. Featuring the final screen “appearance” of horror icon Boris Karloff, “Mad Monster Party” was co-written by comics legend Harvey Kurtzman, creator of the original “Mad” comic books, and featured character designs by cartoonist Jack Davis of “Mad Magazine” and EC comics — a genius at combining humor and grotesquerie. The cast also features hair-challenged stand-up comic Phyllis Diller as “the monster’s mate,” pop singer/actress Gayle Garnett as Dr. Frankenstein’s sexy assistant, and voice actor Allen Swift, who performs dopey but amusing impressions of deceased horror stalwarts Peter Lorre and Bela Lugosi, as well as the silliest Jimmy Stewart this side of Dana Carvey (the voice of ultra-dweeb hero, Felix Flanken). Featuring shticky gags, a rock ‘n’ roll band of mop-topped skeletons, and surprisingly catchy ‘60s-style mainstream pop tunes by Maury Laws and director Jules Bass, “Mad Monster Party” is not quite a classic, but definitely required viewing for fans of great stop motion-animation and late-‘60s lunacy. It also has one of the stranger animation credits we’ve ever seen: “choreography by ‘Killer Joe’ Piro.” (Piro was a temporarily famous New York City dance teacher and disco habitué. Rankin-Bass was way too hip to use anything but the latest steps for its monsters.) – Bob Westal

Shinbone Alley (1971)

All but unseen since 1971, “shinbone alley” was released to DVD in 2007, but to this day no one’s banging the drum very loudly for this unusually dark cartoon musical comedy. The film’s roots are in the “archy and mehibital” stories of early 20th century journalist Don Marquis. First published within a year of the 1915 publication of Franz Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” Marquis’s stories were supposedly written by a human poet reincarnated as a cockroach — typed out one letter at a time in verse form by jumping up and down on the keys of Marquis’s typewriter (since a cockroach couldn’t very well operate the shift key of a manual typewriter, no capitals were used.) The stories, which generally concerned Archy’s friendship with an amoral female cat named Mehibital, endured and became the subject of a 1954 musical-comedy concept album, and later a pre-“Cats” Broadway show, co-written by a young Mel Brooks. The theatrical “shinbone alley” ran for an unimpressive 49 performances, but its reputation lingered long enough so that animator John D. Wilson was inspired to make probably the darkest G-rated “family” musical of all time, with references to suicide, illegitimate childbirth and gross parental neglect. Though Mel Brooks was not involved, veteran performers Eddie Bracken and Carol Channing reprised their roles from the album, and were joined by ubiquitous bass-voiced character actor John Carradine (i.e., David, Keith and Robert’s pop) and Alan Reed — the voice of Fred Flintstone. Especially considering its widely panned animation (a single sequence, in the style of original illustrator George Herriman of “Krazy Kat” fame, does win some praise), it’s no surprise that, despite some fascinating aspects, “shinbone alley” has yet to find its audience. – Bob Westal

All but unseen since 1971, “shinbone alley” was released to DVD in 2007, but to this day no one’s banging the drum very loudly for this unusually dark cartoon musical comedy. The film’s roots are in the “archy and mehibital” stories of early 20th century journalist Don Marquis. First published within a year of the 1915 publication of Franz Kafka’s “Metamorphosis,” Marquis’s stories were supposedly written by a human poet reincarnated as a cockroach — typed out one letter at a time in verse form by jumping up and down on the keys of Marquis’s typewriter (since a cockroach couldn’t very well operate the shift key of a manual typewriter, no capitals were used.) The stories, which generally concerned Archy’s friendship with an amoral female cat named Mehibital, endured and became the subject of a 1954 musical-comedy concept album, and later a pre-“Cats” Broadway show, co-written by a young Mel Brooks. The theatrical “shinbone alley” ran for an unimpressive 49 performances, but its reputation lingered long enough so that animator John D. Wilson was inspired to make probably the darkest G-rated “family” musical of all time, with references to suicide, illegitimate childbirth and gross parental neglect. Though Mel Brooks was not involved, veteran performers Eddie Bracken and Carol Channing reprised their roles from the album, and were joined by ubiquitous bass-voiced character actor John Carradine (i.e., David, Keith and Robert’s pop) and Alan Reed — the voice of Fred Flintstone. Especially considering its widely panned animation (a single sequence, in the style of original illustrator George Herriman of “Krazy Kat” fame, does win some praise), it’s no surprise that, despite some fascinating aspects, “shinbone alley” has yet to find its audience. – Bob Westal

The Point! (1971)

Fans of Harry Nilsson have long been aware of his fondness for filthy lyrics and scatological humor – as well as his gift for gentle, tender pop balladry. He was a man of extremes, was Nilsson, which is why it makes perfect sense that one of his most enduring works is a loopy cartoon (and its attendant soundtrack), inspired by a revelation he experienced during an acid trip. To hear Nilsson tell it, he looked at the trees, noticed they came to points, looked at the houses, noticed they had points too, and realized that everything – wait for it – has a point! (And if it doesn’t, then that has a point, too!) The movie is about as goofy as you’d expect for something released in 1971, and the soundtrack meanders, but it contains a number of Nilsson's strongest songs, including “Me and My Arrow,” “Think About Your Troubles,” and “Lifeline.” Distressingly large chunks of Nilsson's catalog fall in and out of print on a regular basis, but you can usually count on “The Point!” being available, and for good reason – even with all its flaws, it’s an eminently charming piece of pleasantly addled innocence. – Jeff Giles

Fans of Harry Nilsson have long been aware of his fondness for filthy lyrics and scatological humor – as well as his gift for gentle, tender pop balladry. He was a man of extremes, was Nilsson, which is why it makes perfect sense that one of his most enduring works is a loopy cartoon (and its attendant soundtrack), inspired by a revelation he experienced during an acid trip. To hear Nilsson tell it, he looked at the trees, noticed they came to points, looked at the houses, noticed they had points too, and realized that everything – wait for it – has a point! (And if it doesn’t, then that has a point, too!) The movie is about as goofy as you’d expect for something released in 1971, and the soundtrack meanders, but it contains a number of Nilsson's strongest songs, including “Me and My Arrow,” “Think About Your Troubles,” and “Lifeline.” Distressingly large chunks of Nilsson's catalog fall in and out of print on a regular basis, but you can usually count on “The Point!” being available, and for good reason – even with all its flaws, it’s an eminently charming piece of pleasantly addled innocence. – Jeff Giles

Down and Dirty Duck (1974)

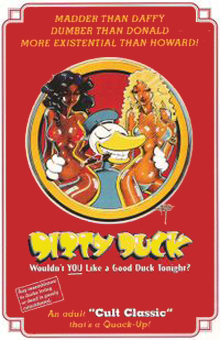

Okay, anything goes in animation – heck, that’s part of its appeal – but even in context, this is strange. Likely assembled as a quick cash-in on the underground success of Ralph Bakshi's “Fritz the Cat,” “Down and Dirty Duck” was put together with the assistance of erstwhile Turtles (and Mothers of Invention) Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan (nee Flo and Eddie), who contributed voice, music and plot elements. (The duo’s former employer, Frank Zappa, makes a cameo appearance during a particularly bizarre segment in which his head rises, sunlike, in the sky over the main characters.) Critics were unmoved, dismissing director/screenwriter Charles Swenson’s work as lacking any redeeming value. It’s an accurate enough description, but whether or not “Dirty Duck” has any redeeming value, it’s still got plenty of comedic value. Dig “Fritz the Cat?” Ever gotten a chuckle out of R. Crumb’s work? See if you can hunt down a copy of “Down and Dirty Duck.” – Jeff Giles

Okay, anything goes in animation – heck, that’s part of its appeal – but even in context, this is strange. Likely assembled as a quick cash-in on the underground success of Ralph Bakshi's “Fritz the Cat,” “Down and Dirty Duck” was put together with the assistance of erstwhile Turtles (and Mothers of Invention) Mark Volman and Howard Kaylan (nee Flo and Eddie), who contributed voice, music and plot elements. (The duo’s former employer, Frank Zappa, makes a cameo appearance during a particularly bizarre segment in which his head rises, sunlike, in the sky over the main characters.) Critics were unmoved, dismissing director/screenwriter Charles Swenson’s work as lacking any redeeming value. It’s an accurate enough description, but whether or not “Dirty Duck” has any redeeming value, it’s still got plenty of comedic value. Dig “Fritz the Cat?” Ever gotten a chuckle out of R. Crumb’s work? See if you can hunt down a copy of “Down and Dirty Duck.” – Jeff Giles

Journey Back to Oz (1974)

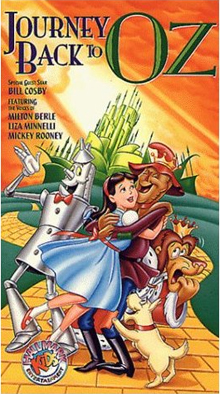

Let’s get this acknowledgment out of the way quickly: “Journey Back to Oz” is not a great movie. The most egregious sin it commits is to play so hard and fast with the plot of the original “Oz” sequel, “The Marvelous Land of Oz,” that L. Frank Baum doesn’t even get a writing credit, even though certain elements and characters were unabashedly borrowed from it. But what makes it worth watching is this absolutely phenomenal list of actors providing voice talent: Mickey Rooney (The Scarecrow), Danny Thomas (The Tin Man), Milton Berle (The Cowardly Lion), Paul Lynde, Ethel Merman, Mel Blanc, Larry Storch, Herschel Bernardi and Jack E. Leonard. There’s also a holdover from the original, with Margaret Hamilton going legit and moving from playing the Wicked Witch of the West to voicing Aunt Em. But the most nostalgic casting comes from giving the role of Dorothy to Liza Minnelli, whose voice is a freaking Xerox of what her mom’s sounded like in 1939. (Too bad the songs that Liza is handed to sing aren’t as memorable.) The animation was done by Filmation, and although even they wouldn’t claim that their material is up to Disney standards, they certainly get points for tenacity, that’s for sure: the dialogue and songs were recorded in ’64, but they had to scrimp and save for the better part of 10 years to finish the animation. – Will Harris

Let’s get this acknowledgment out of the way quickly: “Journey Back to Oz” is not a great movie. The most egregious sin it commits is to play so hard and fast with the plot of the original “Oz” sequel, “The Marvelous Land of Oz,” that L. Frank Baum doesn’t even get a writing credit, even though certain elements and characters were unabashedly borrowed from it. But what makes it worth watching is this absolutely phenomenal list of actors providing voice talent: Mickey Rooney (The Scarecrow), Danny Thomas (The Tin Man), Milton Berle (The Cowardly Lion), Paul Lynde, Ethel Merman, Mel Blanc, Larry Storch, Herschel Bernardi and Jack E. Leonard. There’s also a holdover from the original, with Margaret Hamilton going legit and moving from playing the Wicked Witch of the West to voicing Aunt Em. But the most nostalgic casting comes from giving the role of Dorothy to Liza Minnelli, whose voice is a freaking Xerox of what her mom’s sounded like in 1939. (Too bad the songs that Liza is handed to sing aren’t as memorable.) The animation was done by Filmation, and although even they wouldn’t claim that their material is up to Disney standards, they certainly get points for tenacity, that’s for sure: the dialogue and songs were recorded in ’64, but they had to scrimp and save for the better part of 10 years to finish the animation. – Will Harris

Coonskin (1975)

Ralph Bashki may have earned animation infamy in 1971 when he brought an X-rated feline named Fritz to the silver screen, but it’s arguable that he earned even more controversy four years later. You thought “Song of the South” got people up in arms? Try Bakshi’s adaptation, “Coonskin,” where an African-American rabbit, fox, and bear get into organized crime and deal with corrupt cops, con men, and the Mafia. Unsurprisingly, the Congress of Racial Equality criticized the film for being racist upon its release, but in one of those delightfully ironic moments, they were eventually forced to admit that no one in the organization had actually seen the film. Blending live action with its animation, “Coonskin” provided roles on both sides of the fence for Philip Michael Thomas, Scatman Crothers and the legendary Barry White, but its bold, racially charged imagery resulted in something far less than a box office smash. Nonetheless, critic Leonard Maltin has said of the film, “It remains one of (Bashki’s) most exciting films, both visually and conceptually,” while Quentin Tarantino spent half an hour talking about the flick during the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. (There was also brief chatter about the Wu Tang Clan wanting to produce a “Coonskin 2,” but, alas, that has come to naught.) Bashki himself has shrugged off the film’s controversial content, saying, “The only reason for cartooning to exist is to be on the edge. If you only take apart what they allow you to take apart, you’re Disney.” Unfortunately, it’s also resulted in “Coonskin” remaining unavailable on DVD. – Will Harris

Ralph Bashki may have earned animation infamy in 1971 when he brought an X-rated feline named Fritz to the silver screen, but it’s arguable that he earned even more controversy four years later. You thought “Song of the South” got people up in arms? Try Bakshi’s adaptation, “Coonskin,” where an African-American rabbit, fox, and bear get into organized crime and deal with corrupt cops, con men, and the Mafia. Unsurprisingly, the Congress of Racial Equality criticized the film for being racist upon its release, but in one of those delightfully ironic moments, they were eventually forced to admit that no one in the organization had actually seen the film. Blending live action with its animation, “Coonskin” provided roles on both sides of the fence for Philip Michael Thomas, Scatman Crothers and the legendary Barry White, but its bold, racially charged imagery resulted in something far less than a box office smash. Nonetheless, critic Leonard Maltin has said of the film, “It remains one of (Bashki’s) most exciting films, both visually and conceptually,” while Quentin Tarantino spent half an hour talking about the flick during the 2004 Cannes Film Festival. (There was also brief chatter about the Wu Tang Clan wanting to produce a “Coonskin 2,” but, alas, that has come to naught.) Bashki himself has shrugged off the film’s controversial content, saying, “The only reason for cartooning to exist is to be on the edge. If you only take apart what they allow you to take apart, you’re Disney.” Unfortunately, it’s also resulted in “Coonskin” remaining unavailable on DVD. – Will Harris

Watership Down (1978)

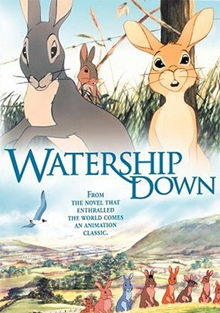

For an animated movie about a group of rabbits, “Watership Down” is incredibly heady stuff, combining elements of “The Great Escape,” “1984” and even “The Lorax.” Based on the novel by Richard Adams, the film finds a group of rabbits fleeing their warren when Fiver, a runt with borderline psychic abilities, envisions the death of the entire warren. (Soon after, developers destroy the warren.) The trek to Watership Down, the warren in Fiver’s vision, is not an easy one, as they have to avoid hawks, snares, farmers and even other rabbits in order to survive. They enlist the help of an injured seagull to help the group look for does, and he tells them their best chance is to infiltrate the fascist Efrafa warren, run by the monstrous General Woundwort. Death is quite literally nipping at the rabbits’ heels throughout, and even shows up as a minor character (the black rabbit Inle, which scared the daylights out of us as children). The animators chose a naturalistic approach to most of the movie (save the cartoonish intro), and it has held up extremely well. The scene where Fiver hunts for his injured brother Hazel, scored to the tune of Art Garfunkel’s “Bright Eyes,” is one of the most sadly beautiful moments in animation history. There has since been a 39-episode “Watership Down” animated TV series, which expands upon the universe established within Adams’ novel, but it can’t touch the original film. – David Medsker

For an animated movie about a group of rabbits, “Watership Down” is incredibly heady stuff, combining elements of “The Great Escape,” “1984” and even “The Lorax.” Based on the novel by Richard Adams, the film finds a group of rabbits fleeing their warren when Fiver, a runt with borderline psychic abilities, envisions the death of the entire warren. (Soon after, developers destroy the warren.) The trek to Watership Down, the warren in Fiver’s vision, is not an easy one, as they have to avoid hawks, snares, farmers and even other rabbits in order to survive. They enlist the help of an injured seagull to help the group look for does, and he tells them their best chance is to infiltrate the fascist Efrafa warren, run by the monstrous General Woundwort. Death is quite literally nipping at the rabbits’ heels throughout, and even shows up as a minor character (the black rabbit Inle, which scared the daylights out of us as children). The animators chose a naturalistic approach to most of the movie (save the cartoonish intro), and it has held up extremely well. The scene where Fiver hunts for his injured brother Hazel, scored to the tune of Art Garfunkel’s “Bright Eyes,” is one of the most sadly beautiful moments in animation history. There has since been a 39-episode “Watership Down” animated TV series, which expands upon the universe established within Adams’ novel, but it can’t touch the original film. – David Medsker

The Phantom Tollbooth (1979)

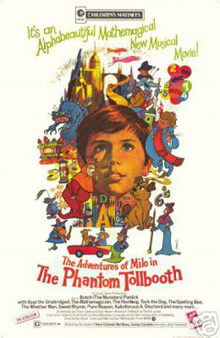

It’s a little sad to realize that Chuck Jones, who gave the world some of movie history’s most transcendently hilarious short-form animation through innumerable Warner Brothers classics, including “One Froggy Evening” and “Duck Dodgers in the 24½ Century,” only headed up one feature length production, this 1970 film version of Norton Juster’s popular 1961 children’s novel. Adapting the book, which combines educational allegory and “Alice in Wonderland”-style satiric fantasy, “The Phantom Tollbooth” is bookended with live action sequences featuring teenage television star Butch Patrick, for once liberated from his Eddie Munster widow’s peak. As the young hero, Milo enters an alternate, animated universe through a mysterious gateway. Once there, he encounters a cast of wacky and strange characters voiced by four of the most famously versatile voice actors in animation history: Mel “Bugs Bunny” Blanc, Daws “Yogi Bear” Butler, June “Rocky the Flying Squirrel” Foray, and Hans “Snidely Whiplash” Conried. With live-action sequences directed by first-timer Dave Monahan (on his only film) and with animation co-directed by Jones’ Warner Brothers cohort Abe Levitow (who also directed “Gay Purr-ee”), “The Phantom Tollbooth” generally receives fairly high marks for its animation, and for Chuck Jones’ zany wit, as well as some very 1970 psychedelic touches. On the other hand, some fans miss the style of the book’s original illustrations by cartoonist Jules Feiffer. (Nortan Juster was also reportedly less than thrilled with the adaptation.) As it turned out, Chuck Jones’ only feature was apparently foredoomed to box office defeat because of the ongoing financial crisis at MGM, which caused it to be released only to special children’s matinees. Unavailable since a 1992 VHS release, “The Phantom Tollbooth” is expected to be reissued on DVD sometime next year. – Bob Westal

It’s a little sad to realize that Chuck Jones, who gave the world some of movie history’s most transcendently hilarious short-form animation through innumerable Warner Brothers classics, including “One Froggy Evening” and “Duck Dodgers in the 24½ Century,” only headed up one feature length production, this 1970 film version of Norton Juster’s popular 1961 children’s novel. Adapting the book, which combines educational allegory and “Alice in Wonderland”-style satiric fantasy, “The Phantom Tollbooth” is bookended with live action sequences featuring teenage television star Butch Patrick, for once liberated from his Eddie Munster widow’s peak. As the young hero, Milo enters an alternate, animated universe through a mysterious gateway. Once there, he encounters a cast of wacky and strange characters voiced by four of the most famously versatile voice actors in animation history: Mel “Bugs Bunny” Blanc, Daws “Yogi Bear” Butler, June “Rocky the Flying Squirrel” Foray, and Hans “Snidely Whiplash” Conried. With live-action sequences directed by first-timer Dave Monahan (on his only film) and with animation co-directed by Jones’ Warner Brothers cohort Abe Levitow (who also directed “Gay Purr-ee”), “The Phantom Tollbooth” generally receives fairly high marks for its animation, and for Chuck Jones’ zany wit, as well as some very 1970 psychedelic touches. On the other hand, some fans miss the style of the book’s original illustrations by cartoonist Jules Feiffer. (Nortan Juster was also reportedly less than thrilled with the adaptation.) As it turned out, Chuck Jones’ only feature was apparently foredoomed to box office defeat because of the ongoing financial crisis at MGM, which caused it to be released only to special children’s matinees. Unavailable since a 1992 VHS release, “The Phantom Tollbooth” is expected to be reissued on DVD sometime next year. – Bob Westal

The Last Unicorn (1982)

For a movie that only earned $6 million and change when it was released, “The Last Unicorn” has certainly gone on to enjoy quite a large post-theatrical following – particularly in Germany, where it’s shown on television every Christmas. While it’s easy to see why parents might have avoided “Unicorn” when it was released in 1982 (it’s dark enough to make other early ‘80s ‘toons like “The Secret of N.I.M.H” look like the most madcap of Looney Tunes) it’s just as easy to understand the movie’s enduring appeal. The script, adapted from Peter Beagle’s novel, was strong enough to attract voicework from Hollywood luminaries such as Mia Farrow, Jeff Bridges, Christopher Lee, Angela Lansbury and Alan Arkin, long before it became trendy for stars to lend their pipes to kids’ fare. (The filmmakers even got Jimmy Webb and America to do the soundtrack! In 1982!) After years of American neglect, “The Last Unicorn” finally got its DVD due last year, with a remastered 25th anniversary edition. Unfortunately, even the restored version mutes the original’s few scattered uses of the word “damn” (as in damn, Granada International, don’t you trust us to decide what’s okay for our kids to watch?). – Jeff Giles

For a movie that only earned $6 million and change when it was released, “The Last Unicorn” has certainly gone on to enjoy quite a large post-theatrical following – particularly in Germany, where it’s shown on television every Christmas. While it’s easy to see why parents might have avoided “Unicorn” when it was released in 1982 (it’s dark enough to make other early ‘80s ‘toons like “The Secret of N.I.M.H” look like the most madcap of Looney Tunes) it’s just as easy to understand the movie’s enduring appeal. The script, adapted from Peter Beagle’s novel, was strong enough to attract voicework from Hollywood luminaries such as Mia Farrow, Jeff Bridges, Christopher Lee, Angela Lansbury and Alan Arkin, long before it became trendy for stars to lend their pipes to kids’ fare. (The filmmakers even got Jimmy Webb and America to do the soundtrack! In 1982!) After years of American neglect, “The Last Unicorn” finally got its DVD due last year, with a remastered 25th anniversary edition. Unfortunately, even the restored version mutes the original’s few scattered uses of the word “damn” (as in damn, Granada International, don’t you trust us to decide what’s okay for our kids to watch?). – Jeff Giles

Fire and Ice (1983)

After making his name bringing the world of underground comics to movie theaters in the early ‘70s, Ralph Bakshi moved on to the increasingly popular “sword & sorcery” genre. First was the transitional Vaughn Bode-esque satirical fantasy, “Wizards,” and from there it was to his abortive 1978 attempt at “Lord of the Rings.” After taking a well-timed break from the genre, he tried his hand again with 1983’s “Fire and Ice,” an all but forgotten collaboration with muscle-obsessed fantasy artist Frank Frazetta, along with Roy Thomas and Gerry Conway -- two of the writers of the extremely popular Marvel comics incarnation of Robert E. Howard’s “Conan the Barbarian.” The story wasn’t anything new — something about an evil wizard, an ice mountain, a couple of muscle bound dudes, and a buxom maiden in a string bikini. The gimmick here was that the entire film was rotoscoped, so thank you once again, Max Fleischer. For the record, Richard Linklater’s “A Scanner Darkly” also used the technique, but the animation in “Fire and Ice,” which is far more traditionally comic-book-like than either Linklater’s films or Bakshi’s earlier rotoscoping in “Lord of the Rings,” is outstanding by the lackluster standards of ‘80’s animation. While few call it “great,” or even “good,” the film has its fans among hardcore animation heads. It also proves that “300” isn’t the first possibly homoerotic film to feature men who are able to fight mostly naked in the snow without developing severe hypothermia or frostbite. – Bob Westal

After making his name bringing the world of underground comics to movie theaters in the early ‘70s, Ralph Bakshi moved on to the increasingly popular “sword & sorcery” genre. First was the transitional Vaughn Bode-esque satirical fantasy, “Wizards,” and from there it was to his abortive 1978 attempt at “Lord of the Rings.” After taking a well-timed break from the genre, he tried his hand again with 1983’s “Fire and Ice,” an all but forgotten collaboration with muscle-obsessed fantasy artist Frank Frazetta, along with Roy Thomas and Gerry Conway -- two of the writers of the extremely popular Marvel comics incarnation of Robert E. Howard’s “Conan the Barbarian.” The story wasn’t anything new — something about an evil wizard, an ice mountain, a couple of muscle bound dudes, and a buxom maiden in a string bikini. The gimmick here was that the entire film was rotoscoped, so thank you once again, Max Fleischer. For the record, Richard Linklater’s “A Scanner Darkly” also used the technique, but the animation in “Fire and Ice,” which is far more traditionally comic-book-like than either Linklater’s films or Bakshi’s earlier rotoscoping in “Lord of the Rings,” is outstanding by the lackluster standards of ‘80’s animation. While few call it “great,” or even “good,” the film has its fans among hardcore animation heads. It also proves that “300” isn’t the first possibly homoerotic film to feature men who are able to fight mostly naked in the snow without developing severe hypothermia or frostbite. – Bob Westal

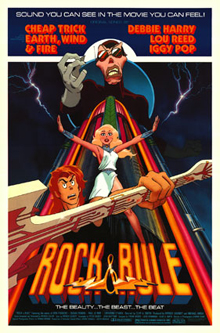

Rock & Rule (1983)

They don’t get much stranger than this one. Canadian animation studio Nelvana and director Clive Smith began this 1983 project as a humorous family film called “Drats!,” but it somehow evolved into a post-apocalyptic tale of satanic magic and the rock and roll lifestyle among mutated, extremely anthropomorphic, cats, dogs, and rats -- with music by Cheap Trick, Lou Reed, Deborah Harry, Iggy Pop, Earth, Wind & Fire and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir (okay, we made the last one up). The film was plagued with endless problems, including (what even the film’s biggest fans admit is) a less than logical storyline, a lawsuit brought by Mick Jagger (the villain’s name: “Mok Swagger”) and the ongoing financial troubles of MGM, its disastrous first release was followed by a drastically recut, retitled version which, naturally, didn’t do any better. Just to add spice to the whole mess, the original negative was supposedly lost in a fire and the film appeared to be heading toward oblivion. Still, as is sometimes the way in the world of geek cinema, because of its animation (pretty terrific by the standards of the time) and the involvement of some of the most important figures in pop music history, the film has found a small cult following. “Rock & Rule” fans were rewarded for their patience in 2005 with a fully restored deluxe two-DVD boxed set with tons of extras. See, some post-apocalyptic tales of mutated, rock ‘n’ roll-playing cats and dogs do have happy endings. – Bob Westal

They don’t get much stranger than this one. Canadian animation studio Nelvana and director Clive Smith began this 1983 project as a humorous family film called “Drats!,” but it somehow evolved into a post-apocalyptic tale of satanic magic and the rock and roll lifestyle among mutated, extremely anthropomorphic, cats, dogs, and rats -- with music by Cheap Trick, Lou Reed, Deborah Harry, Iggy Pop, Earth, Wind & Fire and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir (okay, we made the last one up). The film was plagued with endless problems, including (what even the film’s biggest fans admit is) a less than logical storyline, a lawsuit brought by Mick Jagger (the villain’s name: “Mok Swagger”) and the ongoing financial troubles of MGM, its disastrous first release was followed by a drastically recut, retitled version which, naturally, didn’t do any better. Just to add spice to the whole mess, the original negative was supposedly lost in a fire and the film appeared to be heading toward oblivion. Still, as is sometimes the way in the world of geek cinema, because of its animation (pretty terrific by the standards of the time) and the involvement of some of the most important figures in pop music history, the film has found a small cult following. “Rock & Rule” fans were rewarded for their patience in 2005 with a fully restored deluxe two-DVD boxed set with tons of extras. See, some post-apocalyptic tales of mutated, rock ‘n’ roll-playing cats and dogs do have happy endings. – Bob Westal

The Black Cauldron (1985)

It seemed like a good idea at the time. After years of catering to the family market, i.e. little kids and their parents, Disney decided to try their hand at a slightly more mature type of animated film, geared toward the teen demographic and higher. Based on the second book in Lloyd Alexander's Chronicles of Prydain saga, “The Black Cauldron” tells of a young lad named Taran who finds himself on an epic adventure to find the mysterious Black Cauldron and prevent it from falling into the hands of the evil Horned King. It’s a sword-and-sorcery epic which has enough in common with both the “Harry Potter” books as well as the works of Tolkien (there’s a creature named Gurgi whose voice is eerily similar to Gollum) to be a success in theaters nowadays, but this is now and that was then, which you might think explains why “The Black Cauldron” proved to be a box office failure. It also didn’t exactly help that Disney never fully committed to the concept of playing to an older crowd. Jeffrey Katzenberg, chairman of Disney at the time, cut several scenes from the final cut of the film – mostly for violence, but one yanked shot involved a partially-nude princess – in order to avoid alienating the company’s core audience; additionally, it’s distracting that, for as dark as the film’s tone grows at times, there always seems to be a cute little Disney character popping up to unnecessarily lighten it up. As a result, “The Black Cauldron” can be a frustrating viewing experience, but it works so well when it does work that you wish Disney hadn’t given up so quickly on the “big kids” market. Unfortunately, it’s clearly a lost cause: the special features on the DVD release of the film include a Donald Duck cartoon. Not exactly what you’d call playing to the teens. – Will Harris

It seemed like a good idea at the time. After years of catering to the family market, i.e. little kids and their parents, Disney decided to try their hand at a slightly more mature type of animated film, geared toward the teen demographic and higher. Based on the second book in Lloyd Alexander's Chronicles of Prydain saga, “The Black Cauldron” tells of a young lad named Taran who finds himself on an epic adventure to find the mysterious Black Cauldron and prevent it from falling into the hands of the evil Horned King. It’s a sword-and-sorcery epic which has enough in common with both the “Harry Potter” books as well as the works of Tolkien (there’s a creature named Gurgi whose voice is eerily similar to Gollum) to be a success in theaters nowadays, but this is now and that was then, which you might think explains why “The Black Cauldron” proved to be a box office failure. It also didn’t exactly help that Disney never fully committed to the concept of playing to an older crowd. Jeffrey Katzenberg, chairman of Disney at the time, cut several scenes from the final cut of the film – mostly for violence, but one yanked shot involved a partially-nude princess – in order to avoid alienating the company’s core audience; additionally, it’s distracting that, for as dark as the film’s tone grows at times, there always seems to be a cute little Disney character popping up to unnecessarily lighten it up. As a result, “The Black Cauldron” can be a frustrating viewing experience, but it works so well when it does work that you wish Disney hadn’t given up so quickly on the “big kids” market. Unfortunately, it’s clearly a lost cause: the special features on the DVD release of the film include a Donald Duck cartoon. Not exactly what you’d call playing to the teens. – Will Harris

When The Wind Blows (1986)

If you were a kid in America in the 1980s, you remember the trauma that the TV movie "The Day After" caused as it reminded us that the possibility of nuclear war was very real, indeed. One might comfortably suggest that the British equivalent of the film was a darkly humorous animated motion picture entitled "When the Wind Blows," based on a graphic novel by Raymond Briggs, which offers a look at how an elderly couple deal with impending war and, once it actually comes to pass, the inevitable aftermath. Indeed, it might even be more disconcerting, as its predominant focus is on how little hope that the survivors of a nuclear holocaust would likely have. Sir John Mills and Dame Peggy Ashcroft provide the voices of the couple, who put their utmost faith in everything the government has told them about how to survive an attack; they've seen much in their time, having survived World War II, so they manage to keep their sprits up even while preparing for the worst. (When the wife fears putting out the good pillows, lest they get fingerprints all over them, her husband replies, "I wouldn't worry about that, love. I imagine they'll get dusty anyway, what with all the fallout.") Unfortunately, their faith serves them poorly, as promises of post-attack government assistance of food and fresh water come to naught, leaving them to collect rain water and ultimately succumb to the ravages of radiation sickness. Director Jimmy Murakami, who also helmed a lovely adaptation of another Briggs classic, "The Snowman," manages to provide the appropriately apocalyptic visions of the attack itself while still making time for sweet flashback sequences to establish the longstanding love the couple have for each other. Alas, the inevitable result is still an excruciating trip to the finale of the film, as we watch husband and wife grow sick and, we can rest assured, eventually die in each others' arms. No, it's not a film for children (and not just because things move at a slow, studied pace that would put pre-teens to sleep), but the statement made by "When the Wind Blows" is one that still proves all too familiar today: war is Hell. – Will Harris

If you were a kid in America in the 1980s, you remember the trauma that the TV movie "The Day After" caused as it reminded us that the possibility of nuclear war was very real, indeed. One might comfortably suggest that the British equivalent of the film was a darkly humorous animated motion picture entitled "When the Wind Blows," based on a graphic novel by Raymond Briggs, which offers a look at how an elderly couple deal with impending war and, once it actually comes to pass, the inevitable aftermath. Indeed, it might even be more disconcerting, as its predominant focus is on how little hope that the survivors of a nuclear holocaust would likely have. Sir John Mills and Dame Peggy Ashcroft provide the voices of the couple, who put their utmost faith in everything the government has told them about how to survive an attack; they've seen much in their time, having survived World War II, so they manage to keep their sprits up even while preparing for the worst. (When the wife fears putting out the good pillows, lest they get fingerprints all over them, her husband replies, "I wouldn't worry about that, love. I imagine they'll get dusty anyway, what with all the fallout.") Unfortunately, their faith serves them poorly, as promises of post-attack government assistance of food and fresh water come to naught, leaving them to collect rain water and ultimately succumb to the ravages of radiation sickness. Director Jimmy Murakami, who also helmed a lovely adaptation of another Briggs classic, "The Snowman," manages to provide the appropriately apocalyptic visions of the attack itself while still making time for sweet flashback sequences to establish the longstanding love the couple have for each other. Alas, the inevitable result is still an excruciating trip to the finale of the film, as we watch husband and wife grow sick and, we can rest assured, eventually die in each others' arms. No, it's not a film for children (and not just because things move at a slow, studied pace that would put pre-teens to sleep), but the statement made by "When the Wind Blows" is one that still proves all too familiar today: war is Hell. – Will Harris

Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland (1989)

He may not be quite the attraction he was back in the early 1900s, when Winsor McKay was drawing his adventures for the weekly comic strip on which this film is loosely based, but Little Nemo is still a beloved icon to a lot of people. (Check out the graphic novel section of your local bookstore the next time you visit, in order to marvel at the various lovingly assembled tributes to McKay’s work that have been issued in recent years.) Japanese filmmaker Fujioka Yutaka was one such person; he approached George Lucas as far back as 1978 to help him get “Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland” off the ground, later taking the script to Chuck Jones, then Gary Kurtz. The film passed through so many hands it would take an entire feature to talk about them all, which is why its eventual Japanese release in 1989 was something of a minor miracle. Of course, that didn’t mean that the American release, in 1992, was successful; quite the opposite, in fact, which is why you may have never heard of it. To be fair, it’s got absolutely nothing on McKay’s original creations, but as a slice of early-‘90s kid-friendly animation, it’s deserving of the home-market cult that’s developed around it. Used copies have been known to fetch upwards of $80 on Amazon and/or eBay. Admit it – you’re a little curious now, aren’t you? – Jeff Giles

He may not be quite the attraction he was back in the early 1900s, when Winsor McKay was drawing his adventures for the weekly comic strip on which this film is loosely based, but Little Nemo is still a beloved icon to a lot of people. (Check out the graphic novel section of your local bookstore the next time you visit, in order to marvel at the various lovingly assembled tributes to McKay’s work that have been issued in recent years.) Japanese filmmaker Fujioka Yutaka was one such person; he approached George Lucas as far back as 1978 to help him get “Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland” off the ground, later taking the script to Chuck Jones, then Gary Kurtz. The film passed through so many hands it would take an entire feature to talk about them all, which is why its eventual Japanese release in 1989 was something of a minor miracle. Of course, that didn’t mean that the American release, in 1992, was successful; quite the opposite, in fact, which is why you may have never heard of it. To be fair, it’s got absolutely nothing on McKay’s original creations, but as a slice of early-‘90s kid-friendly animation, it’s deserving of the home-market cult that’s developed around it. Used copies have been known to fetch upwards of $80 on Amazon and/or eBay. Admit it – you’re a little curious now, aren’t you? – Jeff Giles

Bébé's Kids (1992)

Hollywood is full of tragic stories, but Robin Harris’s tale is a particularly sad one. After working his way up through the nightclub trenches as a stand-up comedian, Harris had started to build a sold resume in Hollywood as well, making appearances in “I’m Gonna Get You Sucka,” “House Party,” “Harlem Nights,” and Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” and “Mo’ Better Blues.” The best of both worlds was gleaming on the horizon, however, when Harris was offered the opportunity to make a feature film based on one of his most popular stand-up routines: “Bébé's Kids,” which revolved around his girlfriend, Jamika, forcing him to put up with her friend Bébé's bratty children, who always seemed to be in Jamika’s possession. The Hudlin brothers – Reggie and Warrington – had even agreed to work their “House Party” magic on the film. Unfortunately, Harris died of a heart attack while the film was in pre-production, and the planned live-action flick evolved into an animated homage to Harris’s routines, where Robin (voiced by Faizon Love) takes Jamika, her son Leon, and Bébé's kids to the Fun World amusement park. It was the first animated film to feature an all-black main cast, which was a significant accomplishment, but for some reason, Paramount decided not to offer up much in the way of promotion for the film, and it only did about $8 million at the box office. Talk about a missed opportunity. Director Bruce W. Smith clearly saw “Bébé's Kids” as a tribute not only to Harris but also to Chuck Jones and Tex Avery as well, offering great character designs and sight gags galore. Meanwhile, Reggie Hudlin’s good-natured script is aided immeasurably by a great voice cast, including Nell Carter, John Witherspoon, George Wallace, Louie Anderson and Rich Little. It must be said, however, that it’s still really, really disconcerting to have Bébé's baby open his mouth and hear the voice of Tone Loc emerge. – Will Harris

Hollywood is full of tragic stories, but Robin Harris’s tale is a particularly sad one. After working his way up through the nightclub trenches as a stand-up comedian, Harris had started to build a sold resume in Hollywood as well, making appearances in “I’m Gonna Get You Sucka,” “House Party,” “Harlem Nights,” and Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” and “Mo’ Better Blues.” The best of both worlds was gleaming on the horizon, however, when Harris was offered the opportunity to make a feature film based on one of his most popular stand-up routines: “Bébé's Kids,” which revolved around his girlfriend, Jamika, forcing him to put up with her friend Bébé's bratty children, who always seemed to be in Jamika’s possession. The Hudlin brothers – Reggie and Warrington – had even agreed to work their “House Party” magic on the film. Unfortunately, Harris died of a heart attack while the film was in pre-production, and the planned live-action flick evolved into an animated homage to Harris’s routines, where Robin (voiced by Faizon Love) takes Jamika, her son Leon, and Bébé's kids to the Fun World amusement park. It was the first animated film to feature an all-black main cast, which was a significant accomplishment, but for some reason, Paramount decided not to offer up much in the way of promotion for the film, and it only did about $8 million at the box office. Talk about a missed opportunity. Director Bruce W. Smith clearly saw “Bébé's Kids” as a tribute not only to Harris but also to Chuck Jones and Tex Avery as well, offering great character designs and sight gags galore. Meanwhile, Reggie Hudlin’s good-natured script is aided immeasurably by a great voice cast, including Nell Carter, John Witherspoon, George Wallace, Louie Anderson and Rich Little. It must be said, however, that it’s still really, really disconcerting to have Bébé's baby open his mouth and hear the voice of Tone Loc emerge. – Will Harris

The Iron Giant (1999)

Before he was brought on board at Pixar, Brad Bird (“The Incredibles,” “Ratatouille”) helmed one of the most beloved and acclaimed box-office duds in the history of animation. Based loosely on a children’s book by poet Ted Hughes, this 1999 Cold War-era tale of a boy and his pet giant robot — who just happens to also be a deadly weapon from another planet — has its share of humor, but it also has surprisingly serious and bold antiwar and antigun undertones that might surprise those who see politically conservative themes in Bird’s more recent works. With a funny and moving screenplay by Tim McCanlies that draws on such science fiction classics as “E.T.” and “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” as well as the mythology of Superman, “The Iron Giant” is a masterpiece of traditional 2-D animation that is nevertheless innovative in its seamless use of computer-generated imagery. The CGI designs for the robot recall everything from the 1960’s anime “Gigantor,” to a metallic Saint Bernard. With a voice cast that includes Jennifer Aniston and Harry Connick Jr., “The Iron Giant” also helped launch the brief movie star career of Vin Diesel, who provided the voice of the robot. But no movie’s perfect, right? – Bob Westal

Before he was brought on board at Pixar, Brad Bird (“The Incredibles,” “Ratatouille”) helmed one of the most beloved and acclaimed box-office duds in the history of animation. Based loosely on a children’s book by poet Ted Hughes, this 1999 Cold War-era tale of a boy and his pet giant robot — who just happens to also be a deadly weapon from another planet — has its share of humor, but it also has surprisingly serious and bold antiwar and antigun undertones that might surprise those who see politically conservative themes in Bird’s more recent works. With a funny and moving screenplay by Tim McCanlies that draws on such science fiction classics as “E.T.” and “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” as well as the mythology of Superman, “The Iron Giant” is a masterpiece of traditional 2-D animation that is nevertheless innovative in its seamless use of computer-generated imagery. The CGI designs for the robot recall everything from the 1960’s anime “Gigantor,” to a metallic Saint Bernard. With a voice cast that includes Jennifer Aniston and Harry Connick Jr., “The Iron Giant” also helped launch the brief movie star career of Vin Diesel, who provided the voice of the robot. But no movie’s perfect, right? – Bob Westal

Heinz Tischmeyer

Heinz Tischmeyer

After Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” became the top grossing picture of 1938, Paramount Pictures turned to Disney’s best known competitor, Max Fleischer (animator of the hugely popular Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons) for an animated feature of its own. That was the good news for Fleischer. The bad news was the studio wanted it in less than a year, and “Snow White” had taken three years to complete. Turning to Irish satirist Jonathan Swift’s fantasy classic -- which, strangely enough, had already been transformed into a pro-Communist parable by stop-motion animators in the Soviet Union -- Max and brother Dave Fleischer discarded their original concept of using Popeye as their Gulliver. Instead, they went with a conventionally heroic characterization, relying on timesaving rotoscopes of actor Sam Parker. (If you’re unfamiliar with the concept, rotoscoping was an animation process invented by Max Fleischer that involved tracing over filmed images.) The rushed production was marked by innumerable problems, including a bitter feud between west coast and east coast animators. While no gunplay resulted from the cartoony clash, it didn’t help the final result. When the film was released at Christmas, critics were unimpressed, but the Fleischer shop’s visual invention and broad comedy was enough to make the film a hit; animated features were still very much a novelty and Paramount’s gamble actually paid off. A follow-up film, the fanciful musical bug fable, “Hoppity Goes to Town” might have done as well. But it was released on Dec. 9, 1941 -- two days after Pearl Harbor was attacked. These days, “Gulliver’s Travels” gets mixed reviews from animation fans, but at least it’s not hard to see. It has fallen into the public domain and is available on several different DVD editions and even for free, legal

After Walt Disney’s “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” became the top grossing picture of 1938, Paramount Pictures turned to Disney’s best known competitor, Max Fleischer (animator of the hugely popular Betty Boop and Popeye cartoons) for an animated feature of its own. That was the good news for Fleischer. The bad news was the studio wanted it in less than a year, and “Snow White” had taken three years to complete. Turning to Irish satirist Jonathan Swift’s fantasy classic -- which, strangely enough, had already been transformed into a pro-Communist parable by stop-motion animators in the Soviet Union -- Max and brother Dave Fleischer discarded their original concept of using Popeye as their Gulliver. Instead, they went with a conventionally heroic characterization, relying on timesaving rotoscopes of actor Sam Parker. (If you’re unfamiliar with the concept, rotoscoping was an animation process invented by Max Fleischer that involved tracing over filmed images.) The rushed production was marked by innumerable problems, including a bitter feud between west coast and east coast animators. While no gunplay resulted from the cartoony clash, it didn’t help the final result. When the film was released at Christmas, critics were unimpressed, but the Fleischer shop’s visual invention and broad comedy was enough to make the film a hit; animated features were still very much a novelty and Paramount’s gamble actually paid off. A follow-up film, the fanciful musical bug fable, “Hoppity Goes to Town” might have done as well. But it was released on Dec. 9, 1941 -- two days after Pearl Harbor was attacked. These days, “Gulliver’s Travels” gets mixed reviews from animation fans, but at least it’s not hard to see. It has fallen into the public domain and is available on several different DVD editions and even for free, legal  Wanna make your toddler grow up real quick? Set the little dickens down in front of the television and put “Animal Farm” in the DVD player. Anyone who read the original source material – George Orwell’s 1945 book of the same name – will already know what horrors they’re embarking upon. But the uninitiated might be shocked at the way Orwell’s political allegory has been transformed by British animators into a blend of Disney-esque animation and moments of legitimate horror, the latter aided immeasurably by Matyas Seiber’s score. The nutshell summary involves a barnyard’s worth of animals that get fed up with the drunken farmer who ostensibly cares for their well-being, and decide to run him out and take control of the farm. Things start out reasonably enough, with the declaration from the elder pig Old Major (inspired by some combination of Marx and Lenin) that “all animals are equal,” but upon his death, another pig named Napoleon (a thinly veiled version of Joseph Stalin) takes the reigns of command and soon adjusts the declaration to include a caveat: “But some animals are more equal than others.” This is definitely not a film for the kiddies. Not only is there acknowledgment of the death of some of the animals during the course of the coup, but when one of the ruling pigs tells the chickens that their eggs will be taken as trade goods, the chickens’ subsequent rebellion results in another motto adjustment: “No animal shall kill another animal…without cause.” In the blood of the chickens! (Let’s not even discuss how Boxer the horse gets a one-way ticket to the glue factory.) The ending of the film is different from the book, offering a successful counter-revolution against Napoleon’s rule. Hmmm, you don’t think that’s because the CIA helped fund the film, do you?